by Mark Lewis Taylor

“Yuri Kochiyama has become an ancestor.” That is how Mumia Abu-Jamal commemorates Yuri Kochiyama in his audio recording this week, “Yuri Kochiyma: A Life in Struggle,” thus giving voice and remembrance to Kochiyama, the Asian-American participant in Afro-Asian and many other U.S. and global movements.

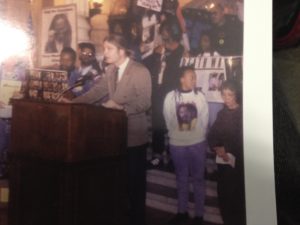

Small of stature though she was, it feels like a giant figure, in one sense, has passed from our midst. And yet, she also leaves a presence, the full force of which so many activists still seek today, a force that unleashes what she called “the togetherness of all peoples.” (Yuri Kochiyama, far right in above photo, having just brought greetings from Malcolm X’s family, with Pam Africa next to her – April 4, 1996. This shows a press conference for Mumia Abu-Jamal in Pennsylvania Capitol Building Rotunda. Robert Meeropol and Julia Wright are also off camera or behind me, shown speaking. The MOVE Organization is in the background holding signs. Personal photo sent to me by friend.)

That notion of “togetherness” might seem trite to some. It may feel like only a general plea to “get along.” And yet, the way Yuri Kochiyama lived this ideal of “the togetherness of all peoples” and the ways she forged her living around political struggle for that “togetherness” under the pressure of an atomizing political system – well, the ideal took on real depth. There was nothing trite about this notion, or about her life.

It is no accident that political prisoner, Abu-Jamal, would commemorate Yuri Kochiyama. Abu-Jamal, who was framed by Philadelphia police and convicted through prosecutorial misconduct for the 1981 murder of policeman Daniel Faulkner, always maintained his innocence.

Precisely those such as Mumia were the focus of Yuri Kochiyama’s work, as she struggled unceasingly for so many political prisoners in the U.S.

Yuri Kochiyama’s life and complexity defy any quick treatment, certainly in this blog or in any one essay. Perhaps the best I can do, here, is to refer you to the biography by Diane C. Fujino, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama, or to her own writing, Passing It On – A Memoir.

My own memories of her involve only one occasion, but it was a memorable one, in April 4 of 1996. I remember how, though slight of frame, her voice filled the rotunda of the Pennsylvania State Capital building where we were holding a press conference in efforts to stop the execution of Mumia Abu-Jamal. After bringing greetings from Malcolm X’s family, she gave in the rotunda a clarion call on behalf of Abu-Jamal. (download my full report made shortly after the 1996 press conference, here).

What was memorable about her speech, though, was that Yuri Kochiyama linked her advocacy for Mumia to the struggles of nearly all other marginalized and oppressed groups and their political prisoners. To be sure, she had a special involvement in struggles for Black freedom in the U.S., for which she had been fighting for years, in the civil rights movement, with Black nationalist groups, with the Jericho movement for political prisoners, with the MOVE 9, before that, working with Malcolm X. She had been present in the Audubon Ballroom in New York City when Malcolm was assassinated in 1965, and in fact was one shown in photo in Life magazine to be cushioning his head from the floor while he lay dying.

But on that day at the rotunda in Pennsylvania in 1995, she linked the struggle for Mumia to that of Puerto Rican independence movements, for American Indian groups, and to those along almost every front seeking lasting freedom for excluded and repressed peoples. Nor was she disconnected from the struggles of Asian and Asian American peoples, having helped with Gloria Lum to organize “Asians for Mumia,” a New York based group, in 1995.

In Mumia, wrote Kochiyama, she found one of the best exemplifications of a principle of human activism that she expressed in her first letter to Malcolm X: the “togetherness of all peoples.” She brought Asian-Americans into the Mumia movement, and she strengthened the Mumia movement with her own and Asian-American communities’ presence. All the while her efforts remained strong for Asian Americans, linking the struggle for Mumia to the efforts of the Justice for Vincent Chin Coalition, and to her role in founding the David Wong Support Committee and more.

What motivated her besides this passion for justice and a hope for “the togetherness of all peoples?” Well, too many things to enumerate here. But it deserves special note that Kochiyama well-remembered the night when her father was snatched by FBI authorities and then the entire family interned in the U.S. mainland. Over a hundred thousand people of Japanese descent in the U.S. were interned in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, over 60 percent of these being U.S. citizens. She and her family and people knew the deep scars left by state violence, its malicious racism against the flesh of unjustly targeted peoples, and – if her life be any guide – the necessity to struggle for life against and amidst it all.

She never forgot victims of U.S. state violence. She did not go silent about their presence. She never stopped fighting. And this is why I like the photo of her fist in the air, reproduced above.

The way she actually began to correspond with Mumia Abu-Jamal warrants recounting. Her own words are the best, as they can be found in Fujino’s biography, The Heartbeat of Struggle:

People won’t believe how Mumia and I got started corresponding. It had nothing to do with the movement. It had nothing to do with political prisoners. I couldn’t believe it but one day I got a letter from him and he wrote in Japanese – Hiragana, which is one of the forms of writing Japanese . . . . And I said how did you learn? And he said he was studying Japanese just by himself in prison. . . . But how this came about was that I had just read something by Velina Houston, the famous Black/Asian/Indian playwright. She wrote about a Black samurai in the sixth or eighth century. And so I wrote to Mumia about him and he said, “You won’t believe it but I’ve just been reading about him myself.” But just before that he wrote in Japanese, and that’s how we got started to know each other. (296-7)

Both Mumia and Yuri, then, exemplify “the togetherness of all peoples,” here in sharing as African- and Asian Americans, respectively, a history of language and literatures, which long pre-dates the founding of the U.S. state and of many of the colonizing European powers that persist today. Both Mumia and Yuri exemplify the kind of revolutionary belonging that builds family with a teeming multitude of revolutionary peoples. And they call to all of us, to keep our movements – for Mumia Abu-Jamal or for any others – deeply rooted in that revolutionary multitude, a multitude ever differentiating and ever liberating, thus making concrete a genuine “togetherness of all peoples.”