“A powerful critique of America as Empire and the challenge it poses for all who believe in the way of Jesus.” James H. Cone, Union Theological Seminary, New York

“Mark Taylor’s absorbing examination of our shameful execution obsession is without a doubt the finest and most discerning theological analysis of the death penalty now available. There is no doubt that the question is once again back in the public eye, and his graphic and penetrating book will surely help focus the discussion we all need.” Harvey Cox, Harvard Divinity School

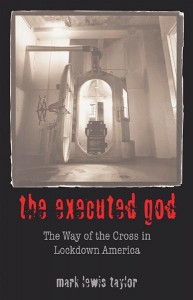

Taylor’s The Executed God stands out as one of the only – surely to date the fullest – treatment by a theologian of U.S. mass incarceration in the context of American social life and U.S. imperial policies. Winner of the Best General Interest Book Award, from the American Theological Association, The Executed God reinterprets Jesus, his journey to execution in a tumultuous period of Roman empire, as a “way of the cross,” a creative, artful mode of challenging political antagonisms.