As a course for students in an institution that educates, primarily, those from predominantly Protestant “Reformed” religious traditions, this course begins with instruction on the content of early Christian founders’ creeds, doctrines, and then turns to the Reformation thinker, John Calvin, primarily his Institutes of the Christian Religion.

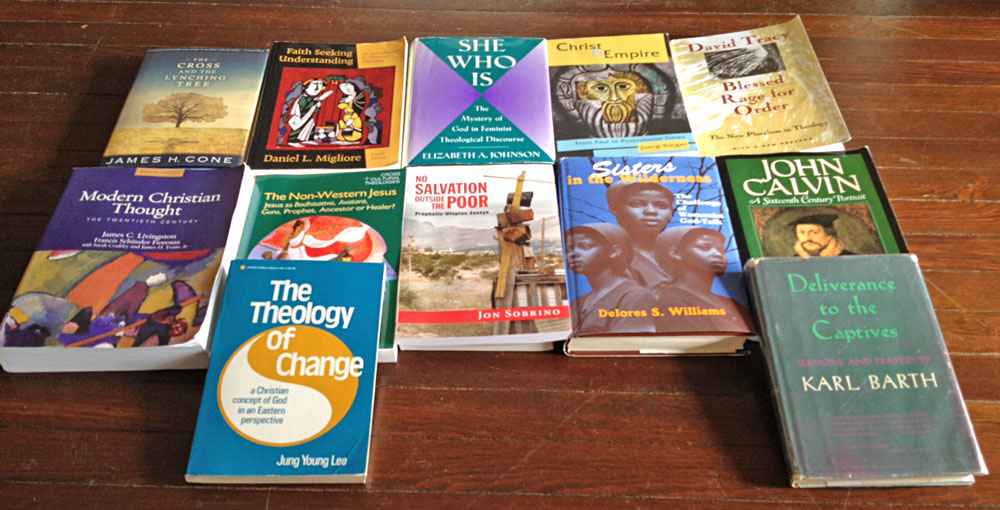

This is only background, though, for introducing the more fully “systematic” move that thinks within the world’s variegated and multilayered contextuality and then also for facing the challenging encounter with other contextual theologies. Just as essential, therefore, as the North Atlantic theologies of figures like Karl Barth, Paul Tillich, and Karl Rahner, are thinkers at work in U.S. Latino/a and Latin American theologies, feminist and womanist traditions, Asian-American, American Indian and Black theologies of liberation. Regarding the latter see the book by James Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree.